Tips & Tricks about family research

Learning from Experience

I’ve tried to include some information from my own experience in this chapter. It’s simple, pragmatic, and understandable, but without claiming to be comprehensive.

Some fellow researchers have a very narrow-minded view of the whole topic of family research. Often, meticulous attention is paid to ensuring that all sources are recorded and reproduced in accordance with academic standards when published, etc. I say: The important thing is that it’s fun! Not everyone wants to write a dissertation right away. On the other hand, sourcing sources later is not without a lot of effort.

Mistakes are annoying, but unavoidable – even if there are representatives of a different opinion… Here, you’ll need help from fellow researchers. I’ve also provided a few more tips on this topic in the chapters on sources and databases.

Chapters on this page:

1. How or where to start?

2. What sources are available and where can I find them?

3. Databases

4. Reading sources – tips & tricks

5. Professional help

6. Storing information

6.1. Originals

6.2. Computers

6.3. Genealogy programs

7. Images

8. Publishing

1. How or where to get started?

Well, how did I get into this hobby? There are certainly countless reasons why someone might have developed this hobby. I think my key moment was something in elementary school. I was given the homework to list my ancestors. I asked my mother and grandfather. Both were very open-minded, and I was interested. The result was four or five generations. This was far more than what my classmates had. From then on, this topic never left me alone.

A few things came together through close and distant relatives. In most families, research in this direction had probably already been done. So in our family. Then there were a few family passports. That means, in the beginning, it was all about gathering information, and I typed out a family tree. The whole thing grew quite extensively in a relatively short time. Then, here and there, a question at the registry office. Finally, I went to work at the parish offices with a bag, writing utensils, a prepared work plan, and pre-printed data sheets. I rolled up my sleeves and pored over old books densely written with quill pens. At first, reading the writings wasn’t so easy for me. But that all comes with time.

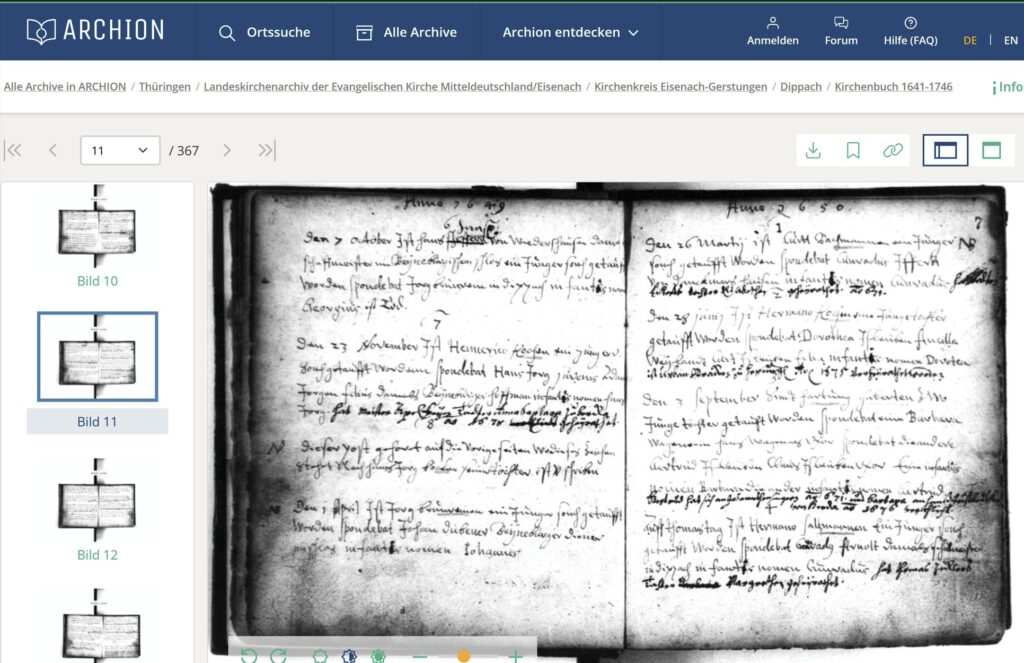

Today, I research on the online church records portal Archion, visit local archives, occasionally browse the internet, and ask questions in forums. Always keeping in mind: Where do I have the biggest gaps, where do I have the highest chance of success, and what is particularly important to me.

I can now look back at a fairly impressive list. I was also fortunate that some of my ancestors came from regions where the church records were not destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War, so in many places the family tree dates back to the 16th century. On the other hand, one-eighth of my ancestors come from Pomerania. Searching here is quite difficult and often unsuccessful.

2. What sources are there and where can I find them?

Here is a small selection of sources. There are, of course, many other sources. Honestly it’s not so easy to translate all of that properly but I try. The storage locations listed here are only a guide and are based on my experience.

- Relatives – even those further away – have already done research, have partial results, or have something to share…

- Family Bibles: If these are still available, they often contain information about family relationships.

- Pictures of relatives ► You should be very accurate with these. Collect everything that has a name. Don’t forget to label them! See also the “Pictures” chapter below.

- Civil registry entries (from 1870) ► Local municipality

- Church books (before 1900) are the most important source before 1870. They record the sacraments (baptism, confirmation/communion, marriage, death), but there are also collective family registers in which all members of a family are listed ► Parish offices, central church archives, or archives. But also via internet portals such as Ancestry.com

- Military capability lists (“Musterungslisten”) ► State archives

- Citizen lists ► Local archives or state archives

- Tax records ► Depending on the origin, state archives, local archives, or church archives

- Real estate purchase/sale records ► Local archives

- Inventories & divisions ► Local archives

- Internet databases…

3. Databases

A differenciation should be made here between two different types of databases:

1. Primary sources (copies of church records, documents, personal directories, etc.)

2. Secondary sources (family trees, pedigrees, local family registers/maps, etc.)

Primary sources are generally preferable to secondary sources. More and more sources are being recorded and made available for viewing and/or downloading from databases. For church registers in Germany, www.archion.de is worth mentioning. The database contains thousands of German – mainly Protestant – church registers. The quality is quite good. There are costs associated with using them and this depends on the length of time they are used. However, the cost is negligible compared to a trip to a parish office. There are also other databases. For example, www.ancestry.com provides a comprehensive, international data collection that goes far beyond church registers. Many registry office documents and emigration or emigration documents are also recorded, although not across the board.

Secondary sources on the internet should generally be treated with caution. While this is widely read, the ever-increasing amount of data available online makes it incredibly tempting to simply accept the data without checking it. On the other hand, this also represents a great opportunity for those who don’t have direct access to the sources. Perhaps an exception to this are the databases and local family books (“OFB”) at www.genwiki.de. In my experience, these are generally quite reliable.

Inaccurate or incorrect data on the internet spreads just as quickly as correct data, as they are blindly and unchecked. Therefore, the same errors can often be found in different databases. This is important to keep in mind. Don’t fall into the trap of believing that if something appears twice or more online, it must be correct.

One approach could therefore be to collect the relevant data and then verify it for accuracy using original sources. The owner of the database or information should be consulted. In addition to being a matter of fairness, this has the advantage that the owner of the data can contribute additional or corrective content if necessary. In very rare cases, you will encounter rejection. Anyone who makes their data available online is generally willing to provide information. Even if the provider of the information is not contacted directly, the respective source must be cited when publishing your own data.

So, in principle, collect data, yes, but please document and verify it.

4. Reading Sources – Tips & Tricks

Which sources: As mentioned above, primary sources are generally preferable to secondary sources. The closer they were created to an event, the greater the probability that the information is true. Primary sources include, for example, baptism, marriage, death registers, confirmation registers, etc. Secondary sources include, in addition to secondary literature, such as local family records, internet information, or mapping, family registers in which baptisms are recorded, transcripts of primary sources, or age information in purchase records, etc.

Source recording: As a general rule, write down all sources if possible. Over the years, as sources became for me increasingly difficult to access, I began to collect more and more detailed data. This also helps a lot when you later want to find out where this information came from, especially when trying to uncover errors. This applies to all sources, including those from the internet or oral traditions.

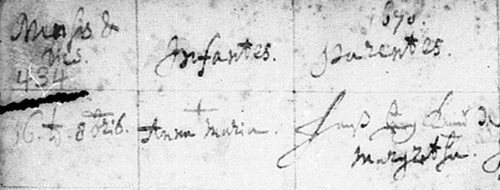

Transcription: Writing off from the original sources as faithfully as possible, and this initial information should be preserved. This can be important if inconsistencies are noticed. These are usually due to incorrect transcriptions from the originals. With faithful transcriptions, this source of error is minimized. Here’s an example: In the original baptismal register from 1670, the following reads: „[Month and day] 16.t[en]. 8bris. [the child:] Anna Maria. [the parents:] Hanß Jerg Knauß Margaretha.“ When copied by an inexperienced researcher or due to carelessness, October 16 (= 16t 8bris) often becomes August 16 (see image on the right).

Unfortunately, I only understood this necessity later and was therefore initially very generous with source recording. This comes back to haunt me later, as processing a certain amount of data becomes extremely time-consuming.

Reading ancient writings: I’ve included this in a separate chapter with some examples.

Interpretations: At some point, everyone comes to a moment where they have to interpret when a source (or several) fails to provide definitive proof or when contradictory statements arise. This should be noted accordingly, indicating that this is a conjecture or speculation. My own experience has shown that interpretations, once made, are very difficult to reverse.

5. Professional Help

There are plenty of genealogists offering their services. I have only a little experience in this area. I’ve only used professional help twice. The fee is either based on the effort involved or on success. Anyone who wants to rely only on this source will have to spend quite a bit of money to get a decent chart.

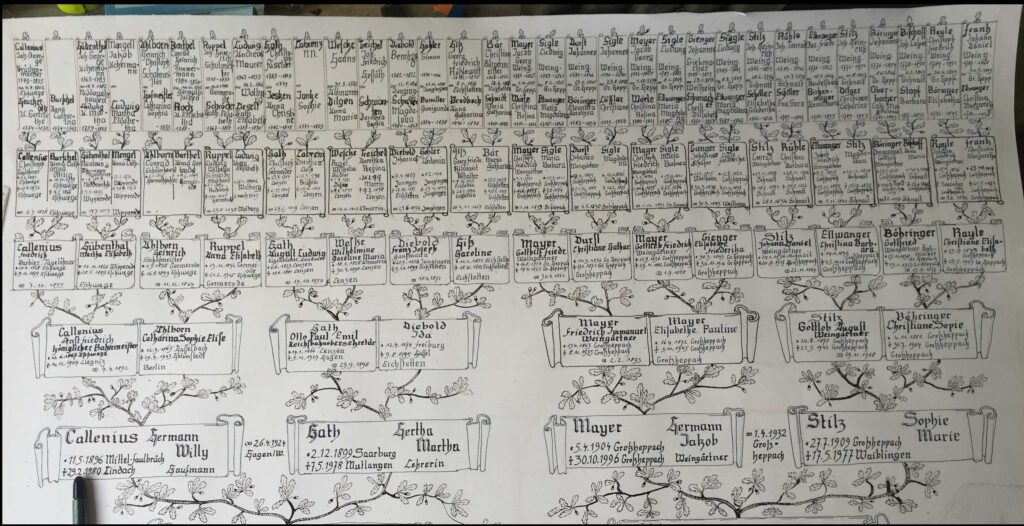

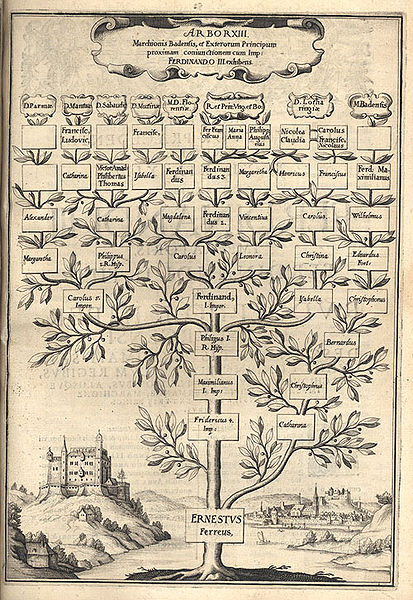

Having a family tree drawn manually is also really not cheap. The reason for this is the time it takes. If you want to give a beautiful gift, you can also paint the trees yourself. This way, you can create a very appealing gift by copying the original. I’ve done this several times and bought some continuous paper for plotters (180gsm, matte). I cut off the required length and started drawing and writing (see image).

6. Saving Information

Storing information seems trivial at first. Just take a computer and save everything. Upon closer inspection, it becomes more complicated: In what format? Database? Images? Backups? Originals? Family sheets? Additional information?

So let’s take it one step at a time:

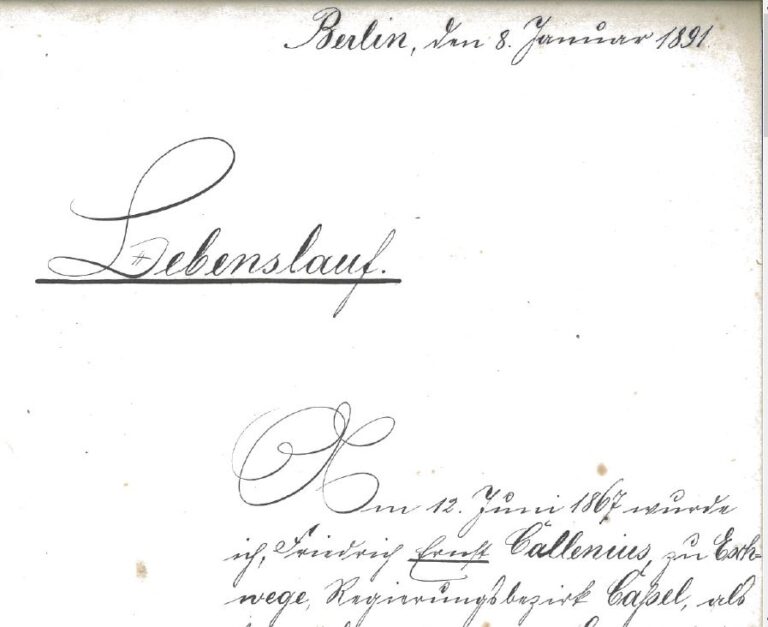

6.1. Originals:

If originals are available, they should be stored in a safe place to protect them from mold (fungus – so dry) and away from light. Anyone interested in more detail can certainly seek professional advice free of charge at the nearest local archive. Originals should also be photographed (e.g., digitally or scanned at a suitable resolution – at least 200 dpi) and stored separately from the originals. Saving storage space is the wrong approach here. For example, I have ancestral passports from teh 1930s. These contain information that could never be retrieved if they were destroyed, as the church records were lost in the war and no copies exist. Therefore, this is the last remaining documentary evidence. These documents are unique. It would be a shame if they were lost through carelessness.

6.2. Computers

Today, computers are an essential tool in genealogy. Despite all the excitement, the question remains: How will the data be readable in the future? As genealogists, we study sources and collect data, some of which is hundreds of years old. This data would surely no longer exist if our forefathers had written it on floppy disks or data tapes.

To preserve the collected works for posterity, a few basic rules should be observed:

– Back up data: Data must be backed up. You need at least one backup copy. And it’s best not to keep the copy where the computer is located (fire, lightning, theft, failure, etc.).

– Programs: Widely used programs and formats should be used. This increases the chance that they can be read over a longer period of time. When new, widely used formats become available, reformat in a timely manner.

– Storage media: The same applies to storage media. Convert backups in a timely manner when there is a change in the storage media. I’m thinking of 5 1/4″ (floppy disks) or 3.5″ disks. Zip drives, etc., were also used for backups—who can read them these days? Not to mention DAT cassettes or audio tapes. Speaking of audio tapes, digitize audio tape recordings as soon as possible. They’re getting a little worse every day.

– Hardware: Don’t just do everything on the computer! Data can be deleted extremely easily these days, destroying a lifetime’s work in seconds. This was hard to imagine in the past. Therefore, I recommend printing out current versions and filing them in a folder. You can also show them to someone!

6.3. Genealogy Program

Entering the information into a database (genealogy program) makes sense simply because it allows for quick and easy data sharing (standardized GEDCOM format). There are many providers in this market. It’s not easy for me to make a recommendation, especially since I’m not familiar with all of them. Here’s an overview of genealogy programs on wiki.genealogy.net.

Generally speaking, you should consider the program you choose as carefully as possible. In my experience, converting data from one program to another is still not possible without loss and therefore involves a lot of manual effort. In some cases, the loss is irreparable. Therefore, the commitment to the programs used is relatively high. I’m going in two directions and using different programs (different programs have different focuses). I use one main program for data entry and storage and have a second one for outputting the data to large whiteboards because this program performs this task better.

My main program used to be the freeware PAF4. Since this program hasn’t been developed for some time, I switched to a new one. I now use “Ages!”. To print family trees, I use the program “Stammbaumdrucker”. So far, I haven’t found a good app for my mobile phone. The disadvantage of all the programs I’ve looked at is that they can’t load existing data. You have to enter it yourself. And that doesn’t make any sense to me. Maybe there is one, but I don’t know it (yet). I’m also registered with Ancestry.com. This can also be helpful, because when you enter the family tree or pedigree, it automatically compares it with other data in the database, and a corresponding message appears. However, you have to be careful here that supposed matches aren’t actually correct.

At the same time, I also enter all the data into a simple Word document. This program is so common that I can be fairly certain that the information will still be readable in many years, and I have security and a cross-reference when converting within different genealogy programs. And I can easily print it out if needed.

In the past, a separate data sheet was created for each family. This can now be done just as easily on a computer. In addition, all other imaginable sources, including scans, images, etc., can be added. Databases now also perform this task.

7. Images

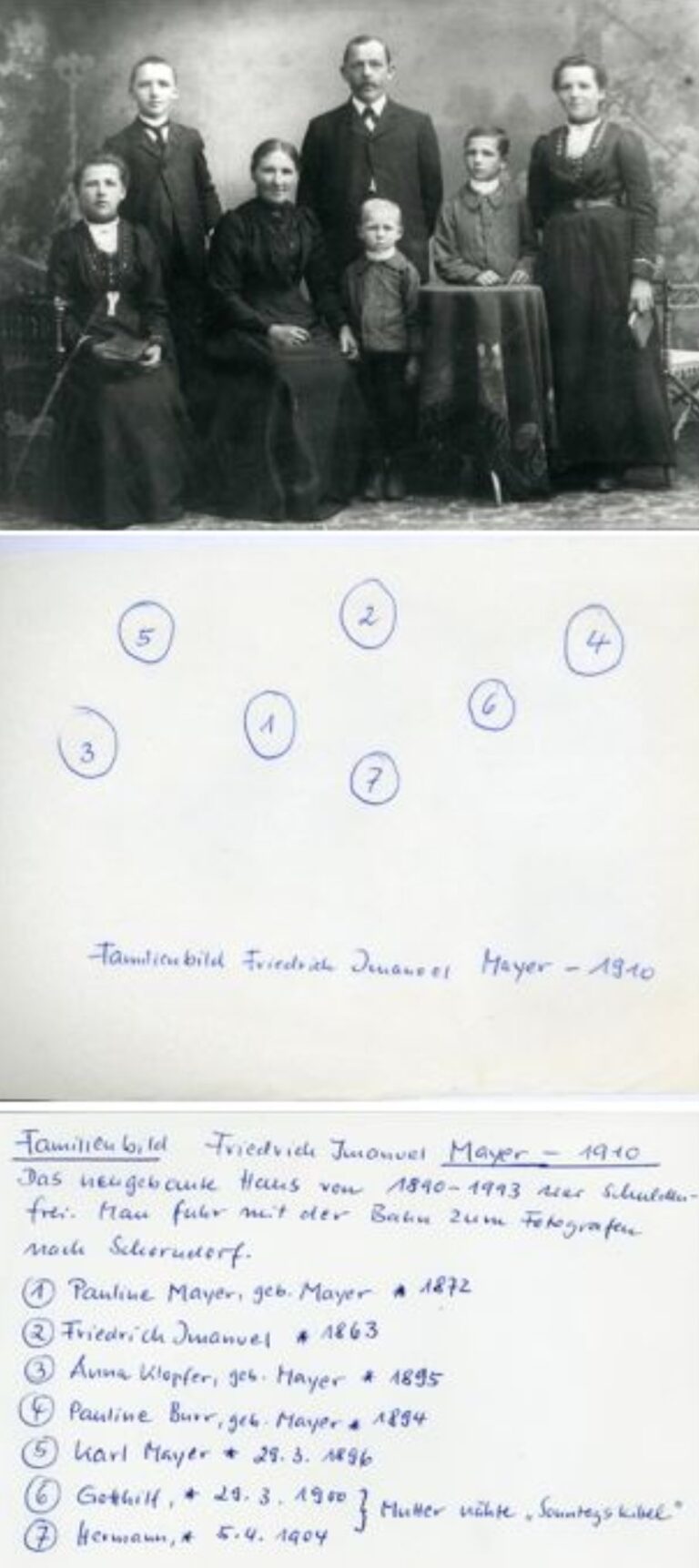

The main problem with old images is missing information. If it’s unclear who or what is shown on the photo, it’s usually worthless for family research. Therefore, here’s a appeal: Collect information and record it for each image. Talking to relatives and friends can help here.

Collect, record and safe the information!

The second problem is securing the images themselves and the associated information. In other words, how to “save” them.

Digital images should, firstly, be saved in a widely used format. This is where the probability of them being readable in the future is greatest. Labeling is a more difficult issue. While there are programs for this, these image formats are (still) very rare, so this is not recommended due to the problem described above (the format is no longer readable or information is lost). Therefore, this should be done either directly on the image/backside (but which changes the image itself) or in a copy. But then you need to store the copy with the picture itself together.

Furthermore, the images should definitely be printed to prevent potential data loss. For more on this topic, see Chapter 6.2, “Computers,” above.

To the right, there’s another three-step way to label the people in the photo. The second step is ideally a (semi-)transparent sheet of paper.

8. Publish?

One goal of family research should, of course, also be to publicize the research results. There are fundamentally different methods for this:

– Online database: This is the simplest method. You simply upload your data to one of the well-known databases – that’s it. However, feedback for your efforts will be relatively limited.

– Book: Write your own book. Then you’ll always have a gift! Your imagination knows no bounds. For example, you can print on demand in extremely small quantities at affordable prices (“print on demand”). There are plenty of providers.

– Your own website: You’re currently sitting in front of one. This requires a bit more knowledge – but I managed it! Here, too, there are hardly any design limitations.

– Family reunions: These opportunities should be used to share your research results. You might also find fellow campaigners and helpers for the topic. You might also discover completely new sources, and you can label images together.

The content, of course, includes the data: who, where, when, for how long, and with whom. Beyond the pure data, however, there’s much more to tell. This lightens things up and makes the whole thing worth reading and interesting. There are also anecdotes to tell everywhere: pictures of relatives or clothes common at the time, about towns and villages. Or you can supplement the pure data with statistical analyses. For example, how many children were common, what was the life expectancy, when people married, what professions existed and what they looked like, and so on… There are hardly any limits here either.

One thing should be kept in mind, however: data from living people may only be collected with their consent.

And now, have fun researching!

Yours, Wolfram Callenius